GHOST IN THE SHELL: WHERE HUMANS GO C-3PO

The Ghost in the Shell franchise began as a Japanese manga series in the late 1980s, but it was the 1995 movie that built its international reputation. By positing a world in which people merge with machines, Ghost in the Shell examines what makes us fundamentally human.

Humanity's Integration with Machines through Oshii’s Eyes

Director Mamoru Oshii wanted a movie that portrayed the “influence and power of computers” by looking at how that influence and power might evolve over time, and the film posits a near future in which humans have begun to merge with machines. Limbs are upgraded with weaponry and other special functions; eyes are replaced with powerful computer-enhanced sensors; minds and memories are expanded via external storage technology.

The inevitable question that arises from all this, of course, is how much artificial enhancement and replacement can a person undergo and still remain fundamentally human?

That’s where the concept of the “ghost” comes in. A ghost is a person’s deep self, his or her essence, which remains intact even as one’s physical body becomes more and more integrated with computers and machines. The name is a reference to philosopher Arthur Koestler’s 1967 book The Ghost in the Machine, a treatise on the nature of consciousness whose title was borrowed from another philosopher, Gilbert Ryle, who coined the phrase to describe the notion of consciousness as somehow apart and separate from biological processes.

The Beginning: Sex & Procreation

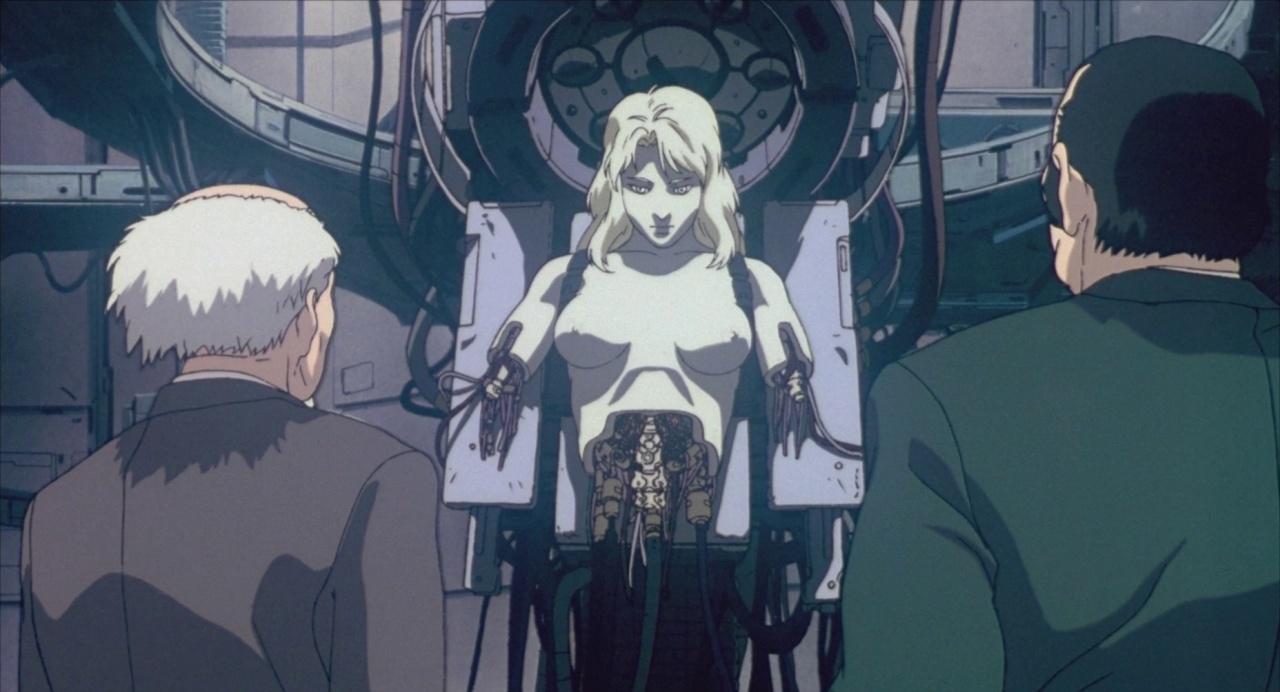

Major Kusanagi leads a unit called Section 9 (akin to secret police) that specializes in cyber-based crime. She and her colleagues are tasked with tracking down a terrorist going after world leaders and hacking into their and other human brains. When we meet Kusanagi in the opening sequence, we learn right away that she loves naked combat.

Why naked? Don’t know. Other people do the optical camouflage thing with clothes on, but not Kusanagi. She’s totally and unabashedly nude, right down to her lack of a vagina. (Sure, she makes a comment in the opening scene, blaming the noise in her head on her period, but that’s just a quippy joke, because she doesn’t have any reproductive organs. Her body’s almost all cyborg, after all.)

Notably, her nudity isn’t sexualized (as we’ve come to expect with an awful lot of anime). There are no leery looks or suggestive comments related to her decision to perform her duties naked (or with her skintight suit). She doesn’t flout her nakedness, but she also doesn’t cover it up, because she’s not ashamed of her Barbie doll anatomy. It just… is.

The union of Kusanagi and the Puppet Master is not sexual or romantic, but rather religious and transcendent. They “slip our bonds and shift to the higher structure.” This is the beginning of a radical and irreversible phase change brought about by the deaths of the living being who became a bit of code inside a brain shell and the bit of code who became a living being. Their deaths and rebirth as a new and separate lifeform (now in the creepy body of a “little girl”) mark the inevitable end of humanity as we know it.

The End: Attaining Death

Kusanagi is, in essence, yet another model of herself living on after the previous version of herself died. She and most of Section 9 are cybernetic beings who must trust that the operators who designed their new bodies kept their ghosts intact. It’s this fact that has Kusanagi wondering who she really is—and whether her ghost is entirely fabricated, or if it’s a distant copy of a copy of the person she once was.

In her discussions with Togusa and Batô, she speculates on meaning and the idea of the self: if all your parts are replaced, do you at some point cease to exist? Are you still you?

The answer, Ghost in the Shell tells us—at least to that latter question—is no. You might be another version of the original you, if that original ever existed, but that’s debatable. Still, the question remains whether that version of you would feel and experience life the same way as the original you did, if ever there was one. And, if you had access to all of those original memories, wouldn’t you at least feel that you were the true version of yourself? As if all those past selves were in the process of becoming you?

But then, what if those original memories are locked away, somewhere deep inside, and you only have the uncertain memories of what once was?

The Middle: I Think. Therefore, Nothing.

Ghost in the Shell explores existential questions of selfhood, the slow vanishing of humanity, and the idea that we will, eventually, become unfeeling machines—desensitized, unempathetic vehicles of progress and self-preservation. Our characters—particularly the emotionless Kusanagi—are often callous, nonchalant, and uncaring.

Atsuko Tanaka’s voicing of Kusanagi, like Iemasa Kayumi as the Puppet Master and much of Akio Ôtsuka’s performance as Batô, is purposefully flat because these characters are unfazed by chaos, violence, sexuality, humor, and tragedy. Kusanagi and other members of Section 9 show no hesitation whatsoever to fire their weapons at large crowds of people. After watching the interrogation with the garbage man who lost his nonexistent family and the self, he thought he was, Kusanagi and Batô are intellectually curious but emotionally unmoved. Their conversations sound at times like two machines comparing notes on topics of existential and epistemological philosophy—that is, questions of existence and of how we know what we know.

Get your tickets for "Ghost in the Shell" (1995) before the machines figure out how to buy them, and we promise not to merge you with any appliances at the concessions! -a night of cyber-philosophical and futuristic times at The Beverly. See you there.

GET TICKETS

To read more;

https://www.vox.com/2017/4/4/15138682/ghost-in-the-shell-anime-philosophy

https://www.theotherfolk.blog/dissections/ghost-in-the-shell

.png)

%402x.svg)